(Reflective Writing) Reflections on my Experience Teaching an Adult Learner

Joining the postgraduate programme in Education also revealed another skill I did not develop in my previous academic programmes. Among the papers I submitted last semester, several of them were reflective writing pieces. It may not be as exhaustive as academic researches. But for me, it has a very useful and practical appeal.

Although I have taught students previously, writing pieces reflecting on my learning and teaching experiences allowed me to connect and synthesise my activities with theoretical concepts I have encountered in my readings. Like a degustation experience at a restaurant, these pieces made me ask why I did this way or why I decided differently? What were the origins of my biases? How did my learner learn, and how was the experience like? And what I could have done better for my next teaching?

Reflections are indeed transformative. Therefore, I encourage everyone, teachers and non-teachers to consider writing reflections - deeper than one's diary entries!

This is my first reflective piece for a volunteer teaching project I participated last semester at the university. Teaching a 'digitally illiterate' when I myself also have limited knowledge of new gadgets tested my character and patience in teaching. Was I successful in the end? And what did I learn in the journey?

Read my reflection below and let me know your thoughts.

=============================

Title: Reflections on my DigiGallus Connect Experience

I will focus this essay on my experiences

and personal reflections as a participant-student partner (“SP”) of DigiGallus

Connect (“organisation”), a largely student-led initiative organised and hosted

at the Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow. The project aims to

drive intergenerational digital inclusion among the Glasgow community

especially for adults 50 years old and above through a mentoring programme

where SPs are paired with a community partner (“CP”) to teach basic digital

skills. Establishing identities,

managing a democratic classroom, building teaching presence and celebrating

milestones in my experience, were the key reasons for the success of my

teaching experience despite the odds and limitations. It will end with a provocation that participating

in such volunteer programmes to support lifelong learning of adults are not only noble, but have helped in connecting me as an international

student to my host community.

Establishing my learners’ identity and managing self-doubt

To become an SP, I participated in

several introductory activities – from virtual orientations introducing the

organisation, to follow-up sessions on Europe’s General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) and learning and teaching behaviours. Once completed, I was given the name and

contact number of my assigned CP, "Douglas" (not his real name). The organisation

provided each CP with a digital tablet inclusive of internet subscription. I

used prepaid Skype call credits to connect with my CP during the five learning

sessions.

There were uneasiness and resistance as I started this journey. As I learned more about the expected outputs and the tasks involved, I questioned whether my current skills were enough to successfully handle the learning sessions. Throughout my life, I am only familiar with two main gadgets – mobile phones (or cellular phones), and laptops. This left me rather doubtful on whether I can carry the task when I have neither held nor owned one.

I experienced some anxiety on how I can establish my learner’s identity. I remember asking myself why a highly globalised and developed country like the United Kingdom would still experience challenges on digital inclusion; and what kind of individuals in this community have no such access. Given that GDPR’s guidelines prohibit sharing of personal information, I wondered how my lack of information about Douglas would affect my teaching given that I do not know who he is, what he is doing and why he signed up for the programme. Would it be considered a violation if I enquired about my student’s activities and why he needs to learn digital skills even if my intentions were to appropriate the learning sessions effectively for him?

I also thought of my learner. Does Douglas even know me? Was he informed that a non-Scottish student at the University will teach these digital skills to him? Can he understand me even if I speak English with a neutral accent? What prior knowledge of computers and digital devices does he have? I wonder how hard it must be on him to participate in such kind of learning activities when I am already challenged by attending my postgraduate modules conducted online. By reflecting on these questions, I became aware of his own limitations aside from my own, and proactively searched for ways to transgress the possible challenges and to ensure that the sessions will be smooth, relevant and meaningful as possible.

As I anticipated the days leading to the first session, my empathy for Douglas even demonstrates my resistance to my earlier intent to apply behaviourism and just allowing him to memorise and remember the steps (Conole, 2008). I understood that my initial doubts reflect with my engagement of Brown’s (2001) argument that credentials and skills over time, have become highly contested spaces for economic participation. Even if I have a postgraduate affiliation and passion for teaching and making a difference in the community, are they enough motivators for me to participate? I thought that they may not be enough to undermine my lack of credentials and technical skills in digital technologies. However, I felt reassured what Dewey (1963) implied that although education is mainly derived through experiences, not all experiences are relevant. Therefore, I can use my own deficiency of experiences to my advantage, use this to transgress defined and existing power structures (Freire, 2005; Hooks, 1994) and develop more creative approaches for my teaching.

Governance in the classroom: Whose interest should prevail?

We agreed to schedule the calls every

Thursday at 11:00 am. On our first learning day, we started by warming up with

each other’s presence. I learned that among the practical skills the

organisation envisions for our CPs to acquire, Douglas wanted to learn just one

thing - how to send emails for his job applications. From an exhaustive line-up

of topics I prepared for him, I literally scrambled and revised my content on

the spot, and taught a topic I was not prepared to do that morning.

Coming to the first learning session, I immediately assumed that I have the agency to decide on what possible learning track Douglas will undertake. I thought whether I should introduce the other practical skills first before his topic of interest. However, I realised that if I only listened to my needs, I undermined his voice because I only focused on my own content and interest to become an effective facilitator. I was not focused on Douglas’ interests to learn and master a desired skill effectively. In solving this dilemma, I learned that putting my learner’s interest, no matter how simple it is, was also equally important.

I decided to make this project an

inclusive conversation between us. I committed to foster an inclusive learning

environment as I believe it builds credence on the part of the teacher, and

reassurance that the learner will not be othered in the learning process (Phirangee

& Malec, 2017). By being inclusive, I also gave

validation to Douglas’ voice on what he hopes to achieve in this programme and

effectively bridge his personal interests and my personal aspirations. This thought

resonates with what Ramdehall et.al’s (2010) suggests that if we want democracy

to be an effective agent of social change, it should also begin in how we

govern our classrooms and recognise voices of everyone. As the teacher, I

thought that in establishing a democratic space for learning, a

social-constructivist pedagogy might be appropriate to become inclusive. In the

process of democratising the learning space, negotiating our respective

interests, and agreeing that Douglas’ learning and mastery be the primary

objective, I also allowed him to be responsible for his own learning outcomes

through various levels of experiences that will gradually build his

understanding and knowledge (Vygotsky,

1978, as cited in Gregson et al., 2015).

Establishing teaching presence requires creativity

We learned that the previous email

address Douglas’ family member gave him was invalid. We recognised that we needed

to start anew and created a new email account. I felt anxious yet excited

because the thought of creating a new email account with someone who is

unfamiliar with operating digital tablets will challenge and push my limits.

However, we were in a voice call. I did not know what was happening to him on the other end. I asked myself does he know what an internet website is? How could he find the email application on the tablet? How did he feel that I am not physically there to help him? How would I manage stress if he gets confused? How could he remember the things I taught him?

In figuring out ways to make teaching work, I exercised my own creativity. And in doing this, I helped my student understand what tools and techniques are essential to complete a task, and gain his mastery and familiarity. I am reminded of the connectivist approach in enabling the learner pick-up the essential information amidst the vast information available (Anderson & Dron, 2012). I asked him to describe those applications and interfaces and read them to me loudly. As we identified the important applications and features, I encouraged him to remember them by taking down notes; and I gave assurance that we will repeat the process until such time that he will be comfortable and familiar with using the gadget.

Using the behaviourist approach, I used the relevant information he gave me to develop a workflow that he will need to remember and practice to develop his familiarity and mastery of the topic. I realised how teacher’s presence and guidance play an essential part in teaching adults to facilitate the knowledge that will be relevant and appropriate to acquire and apply (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007).

Celebrate milestones and look forward

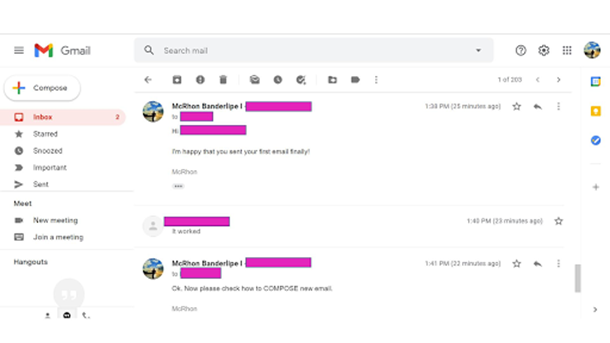

I still remember the time he sent his

first email to me. I was euphoric! I literally screamed with joy when he wrote

to me “it worked.” We then practiced sending emails back and forth during the

sessions that followed. I began teaching him how to add attachments to the

emails. I gradually taught him some basic email writing conventions such as

using salutations when writing formal emails to prospective employers, and how

to properly acknowledge and reply the email. I gave him permission to send test

emails to me when we are not in session. I also encouraged him to explore and

understand the features on his own.

I observed that his engagement with the gadget became more purposeful, as he told me that his family members and friends sent him pictures of their pet animals through email too! The gap between me and him was replaced with a feeling of belongingness. When it was the time to prepare the evaluation report, I became surprised at the feedback he gave. He did not only sent emails to his family but also to contacts outside the community.

There were three factors that encouraged me to participate in this programme. Firstly, I derived from my innate character the need to participate to learn more about my community. When I moved to Singapore eight years ago, I also joined in several volunteering activities to gain new friends, learn about the host country, and dissipate the feeling of loneliness after I left the Philippines. Similarly, I saw an important opportunity to get connected with Glasgow through this platform by understanding various community and intergenerational learning activities that are happening here. Secondly, I observed that I am inclined at participating in various activities supporting older adults and ageing population. My affinity to championing the causes of the elderly is traced on my own personal experiences of assuming caring responsibilities for my father until his passing in 2007. Lastly, this programme came across at a significant time when COVID-19 disrupted our tried-and-tested modes of teaching and facilitation. This project situated my learning against the backdrop of many possible challenges in delivering my sessions while bridging the challenges of physical distance and virtual communication and in creating my identity as adult educator. As I reflected deeply on my experiences, teaching digital skills using only phone calls made me feel inadequate and helpless. In a larger critical narrative however, it provided me several lessons on being a better adult educator especially during this pandemic.

The most important realisation I have learned about this project is that sincere and active participation in learners’ experiences are transformative (Mezirow, 1997). I learned to be aware of the different ways Douglas demonstrates frustration and anxiety. His verbal clues and intonations indicated these emotions. I realised that showing empathy and concern to him when he struggled encouraged him to remain patient and persistent. Giving encouragement, praises and support when learners achieve certain milestones are also important to keep them moving in the learning journey. I felt rewarded for becoming an instrument in making an individual’s simple dream come true. That short email he sent me will be one of the many emails he will send throughout his lifetime. His world will be opened to a universe of possibilities. And it gave me affirmation that I have personally taught a life-changing experience for my student.

To conclude, teaching Douglas made me recognise my own learning abilities and challenges. As I was unfamiliar with the Glaswegian accent, I would regularly ask him to repeat his words so I could understand and take notes. Eventually, I became more comfortable listening to it to the point that I even acquired it. Interestingly, I even recorded myself several times speaking with Glaswegian accent to demonstrate my personal learning gained from this experience. My participation opened the doors to become more involved with the Glaswegian community and allowed me to gain deeper appreciation of the existing challenges of adult learners here in Glasgow. I now felt more belonged to Glasgow by participating in this programme.

Will I participate again? I will; most certainly.

Figure

1. Douglas’ first email to me

REFERENCES:

Anderson,

T., & Dron, J. (2012). Learning Technology through Three Generations of

Technology Enhanced Distance Education Pedagogy, European Journal of Open,

Distance and E-Learning, 2012. European Journal of Open, Distance and

E-Learning, 2. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ992485

Conole, G. (2008). New Schemas for Mapping Pedagogies and Technologies - Ariadne. http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/56/conole/

Dewey, J. (1963). Experience & Education. Collier and Collier Macmillan.

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition (30th Anniv). The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

Gregson, M., Hillier, Y., Biesta, G., Duncan, S., Nixon, L., Spedding, T., & Wakeling, P. (2015). Reflective Teaching in Further, Adult and Vocational Education (4th ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://www.vlebooks.com/Vleweb/Product/Index/2057003?page=0

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12.

Phirangee, K., & Malec, A. (2017). Othering in online learning: an examination of social presence, identity, and sense of community. Distance Education, 38(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1322457

Comments

Thank you for allowing me to take part in this programme. I could say that this was one of the best things that happened to me in my first semester in Glasgow, my university experience at the Uni, and in my introduction to the Scottish community in general.

Looking forward to volunteering again. - McRhon